- Home

- Anne Zouroudi

The Doctor of Thessaly

The Doctor of Thessaly Read online

The Doctor of Thessaly

Anne Zouroudi

For CP

Acta est fabula, plaudite!

. . . There within

she saw that Envy was intent upon

a meal of viper flesh, the meat that fed

her vice . . . And when she saw the splendid goddess dressed

in gleaming armour, Envy moaned: her face

contracted as she sighed. That face is wan,

that body shriveled; and her gaze is not

direct; her teeth are filled with filth and rot;

her breast is green with gall, and poison coats

her tongue. She never smiles except when some

sad sight brings her delight; she is denied

sweet sleep, for she is too preoccupied,

forever vigilant; when men succeed,

she is displeased – success means her defeat.

She gnaws at others and at her own self –

her never-ending, self-inflicted hell . . .

Ovid, Metamorphoses, Book 2 (Translated by Alan Mandelbaum)

Contents

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-one

Twenty-two

Twenty-three

Twenty-four

Twenty-five

Acknowledgements

About the Author

By the Same Author

Dramatis Personae

One

One by one, peal by peal, the joyful church bells fell silent. First, word reached the chapel of St Anna’s; from there, the message passed to St Sotiris’s, where the ringer looped the bell-rope on its hook and set off to her daughter’s for more news. Long before the time agreed, the bells stopped at St George’s on the coast road and at Holy Trinity in the foothills, though for a while, the bell at distant St Paraskevi’s still rang out, its elderly ringer not noticing, in her enthusiasm and her deafness, that all the others were quiet. So they found a bicycle and told the oldest boy to travel quickly; and midway through a celebratory peal, that bell too faltered in its rhythm, and was still.

Across the fields, the buff slopes of the mountains were growing dim. Small waves broke harmlessly on the town beach, and the dark sea stretched towards a sky already pale with evening. The mildness of the afternoon was gone, and a cold breeze raised ripples which ran like shivers across the water.

From the beach head, a woman was making for the sea. The heels of her satin shoes caught between the stones, turning her ankles; but she went determinedly on, carrying the hem of her white gown above her feet, whilst behind, the long train of her dress dragged like a trawl-net, hooking debris left by the high spring tides: brittle kelp and the cap of a beer bottle, the bleached, ovoid bone of a squid, liquorice smears of marine oil.

Close to the sea, the stones were small, becoming shingle at the water’s edge, and beneath the water, sand. As she followed the water-line, her heels sank deep into the shingle, discolouring the shoes with damp. Where three flat rocks stood out from the shallows, she stopped and looked back up the beach, along the road.

No one was there. No one followed.

She turned back to the empty sea. The last good light of day lit her face, picking out the crow’s feet where powdered foundation had set in lines; the trails of mascara-dirtied tears marked her cheeks. In her hands – where raised veins and slender bones stood prominent, and the first brown stains of liver-spots had bloomed – she held two garlands of fake flowers: orange blossoms twisted around paper-covered wire, joined by a length of white ribbon – stefani, the headdresses of a bride and groom.

As hard as she could throw, she cast the garlands away from her on to the sea, expecting them to float on the deep water and drift away to the horizon; but her throw was weak, and the stefani landed in the shallows, where the water quickly turned the delicate flowers ash-grey. The garlands sank, their white ribbon flickering briefly on the surface. Settling on the seabed, their circular shape was lost, shifting and distorted by the water.

Along the road, the street-lamps were lit. Still no one came.

Sinking down on the shingle, she kicked off her satin shoes; and pulling her knees up to her chest, burying her face in the soft skirts of her wedding dress, she wept.

The women gathered at the house (nieces and aunts, cousins, second cousins, neighbours and acquaintances) were reluctant to leave. They didn’t begrudge the care they had taken over clothes and coiffure, the time and money they had wasted; but the aborted wedding was a drama to which they were witnesses, and it seemed harsh, to them, to be asked to leave the scene. They went slowly, muttering to each other behind diamond-ringed hands, carrying their gifts – still wrapped

– in their arms. To Noula, they said nothing; there was no form of words for this occasion.

Noula shut them out, forcing home the bolt on the apartment door. On the salone floor, by the cane-bottomed chairs where they had sat, the musicians’ empty glasses stood beside the whisky bottle they had drained before they left. The plates for the walnut cookies held nothing but crumbs; the roasted peanuts and the pumpkin seeds were all gone, their cracked shells scattered by children across the rugs and into the room’s far corners. A silver tray was still half-filled with long-stemmed glasses of melon liqueur; the tall, ribbon-trimmed candles the pageboys should have carried were abandoned in the window alcove. After the chatter, the laughter and the music, the silence of the room seemed profound.

The room must be put back to how it was before. Chrissa had taken liberties, moving the sofa, changing the tablecloths, rearranging the coffee service in the cabinet.

But all could be quite easily restored. Noula surveyed the work to be done, and smiled.

In the doorway, Aunt Yorgia pulled on a jacket over her black dress. The loose flesh of her upper arms trembled; on the skin of her bony chest, a gold crucifix glittered. With each year, Noula was growing into her likeness; in both her and Chrissa, the legacy of that generation’s women was manifesting: frown-lines and jowls, thread veins and thin lips. The make-up Chrissa had lent Noula had worked no magic, and Chrissa had been right about the greyness in her hair. Perhaps, as Chrissa said, she should have coloured it. But what did it matter, now? Dyeing out the grey had not, in the end, saved Chrissa.

‘I paid the musicians,’ said Aunt Yorgia. ‘I gave them half.’

‘I’ll give you the money.’ Noula’s purse lay on the dresser, beneath the mirror; pulling out banknotes, she turned from her reflection in the glass. ‘There’s enough there for a taxi. You’ll find Panayiotis in the square.’

‘If there’s a blessing in this, it’s that your mother didn’t live to see it, God rest her.’ With three fingertips, Yorgia made the triple cross over her breast, then took the money Noula held out to her. ‘The shame of it would have finished her, for sure. You should get those good clothes off now, and go and find your sister.’

Noula spread her arms to take in the room.

‘How can I leave this mess? There’s a week’s work to be done here, and I’ll get no help from Chrissa. She doesn’t need me running after her. She’ll come home when she’s ready.’

‘With things as they’ve turned out, she’ll never want to come home,’ said Yorgia sharply, ‘and in her position, neither would you. You go and find her, as your mother would want. Fetch her home,

and take good care of her. Be a sister to her, until all this blows over.’

‘But where’s her home to be, Aunt? Up here, alone, or downstairs in the old place, with me?’

Yorgia picked a length of cotton from the shoulder of her jacket.

‘If you can manage to be civil with each other, I should say downstairs, with you,’ she said. ‘Your father paid for this apartment as a dowry.’

‘As my dowry.’

‘As your dowry, because he expected you to be first to marry. As there’s still been no marriage, we’ll keep the dowry ready until there is. Now go and fetch her. There’s only a few minutes before dark. Take her something warm to put on over that dress. It’s cold, now the sun’s gone down. And you be kind to her, Noula. Your sister’s been dealt a hard blow, and we’ll all be made to feel it. Things will be difficult for us all, but we’ll keep our heads high. Ach, Panayia!’ She put her hand to her cheek, remembering. ‘No one’s told the taverna we won’t be coming! I’ll go; I’ll tell the taxi to go round by there. They’ll have to be paid, of course. I’ll tell them you’ll call in, in due course.’

‘Me? Why should I go?’

‘Because,’ said Aunt Yorgia, ‘it would be cruel to make your sister suffer the embarrassment of paying for a wedding breakfast she never got to eat. Don’t let them charge you anything for wine. They won’t have opened any yet, no matter what they say.’

She stepped across to Noula, and placing her hands on Noula’s shoulders, kissed her on both cheeks. Noula smelled the sweetness of old cosmetics, of lipstick and loose powder, the citrus of eau de Cologne. ‘Now go and fetch your sister. Bring her straight home and put her to bed. And make her some camomile tea; it’ll help her sleep. Be kind, Noula. I’ll come and see how she is tomorrow. Your uncle will bring me over in the morning.’

The apartment door banged shut. Aunt Yorgia’s court shoes clattered down the outside stairs and away down the side street, fading into the dusk.

Noula moved to the salone window. The outlook was commonplace, on to a street she had known a lifetime, yet this elevated angle gave it novelty. From here, she could see over the neighbour’s wall into Dmitra’s kitchen, and even to the upper windows of the buildings around the square. Downstairs, where they had always lived, the view was dull, of high walls and their own garden.

She switched on a table lamp she had chosen years ago, and in its light, gazed round the objects that had so long been hers: the soft-cushioned sofa with its matching armchair, the unused china displayed in the cabinet, the Turkish rug woven in burgundy and cream, the lace cloths and doilies relatives had made for her. As the oldest, all this was intended for her – except no suitor had ever come. So when the doctor had asked for Chrissa, Noula was expected to step back and hand her sister everything.

But not now.

In the bedroom, the bed – her bed – was made with embroidered white linens, and on the coverlet, the local girls had formed a heart in sugared almonds. Noula took the almond from the heart’s tip and putting it in her mouth, bit down on the hard, pink coating. No one had listened to her view that, at Chrissa’s age, fertility rites were pointless. The girls had gone through all the rites regardless, scattering handfuls of uncooked rice between the sheets; the grains they had let fall cracked beneath Noula’s feet.

Opening the wardrobe, she ran a hand through Chrissa’s clothes, hung where her own should be: Chrissa’s best dress, Chrissa’s skirts and blouses, Chrissa’s two pairs of shoes placed carefully together, as if Chrissa had been playing house arranging them. On the shelves, she found a cardigan of black wool, and put it aside to take to her sister.

There was nothing of his in the wardrobe, but by the bed was a suitcase battered with use. Pricked by curiosity, she crouched beside it: what had the faithless doctor left behind? A guilty glance to window and door confirmed no one would see, and so she slipped the catches, and raised the suitcase lid.

A scent she didn’t know came off his clothes, a man’s scent, earthy but intriguing. One by one, she lifted out the shirts, the sweaters and the ties, and beneath the trousers found his underpants, large sizes in plain cotton. There were vests, and a washbag with a razor, soap, cologne and ointment used for rheumatism; and, at the very bottom and well concealed, a large, manila envelope, unsealed and unaddressed.

With careful fingers, she extracted the envelope from under his belongings, and without hesitation, withdrew the folded papers it contained.

They were letters of some length, whose opening pages bore the coats of arms of official offices. But the language and the alphabet were foreign, and Noula could make out nothing but the years of their writing: last year, and the year before.

Outside, a motorbike roared past, its rider calling a greeting to someone walking by.

Replacing the letters in the envelope, she repacked the suitcase as best she could, fastening its latches as she closed it.

The letters and their envelope, she kept.

Switching off the lamp which had been hers, she pulled the salone door closed behind her, locked it and pocketed the key. Downstairs, she hid the envelope in a kitchen drawer, and set off to look for Chrissa.

But the suitcase in the bedroom stayed in her mind; for why would the doctor, disappearing, leave most of what he owned behind him?

Two

The hound under the bed scratched at its fleas, rattling the iron bedstead with its haunches. Adonis Anapodos – Adonis Wrong-Way-Round – pushed the blankets from his face, and growled down at the dog – Give over, Vasso; but through the window, the sky was growing light, and so Adonis clambered grumbling from the bed, pushing the dog away when it rose to lick his hand.

There were no rugs on the floors and the unswept tiles were gritty to his feet. So early in the year, the house’s old stone walls still held damp, and as he picked up from the bed-foot the clothes he had worn yesterday, they gave off the earthiness of mildew. He pulled the crumpled trousers over underpants he had slept in for several days, and took his time to match each fly button to its hole; with his shirt he did the same, except where buttons were missing. The pattern on his sweater was marred by snags where thorns had caught it; Adonis made sure the sweater label was to the back, because it often entertained the men to submit him to their inspection, and if anything about him was anapodo, they’d punish him with ridicule and ear-cuffing.

His woollen socks were stuffed inside his boots, and as he unballed the first, a smell rose from it, similar to the foreign cheese in Lambis’s shop. Indifferent to the socks’ stink, he pulled them on, and by his mother’s system (a rough ‘r’ marked inside the right boot’s tongue matched his right hand where, on his little finger, he wore a silver ring), he got his boots correct. By concentrating, he managed both his laces, and calling to the hound to follow him, he went outside.

In the cold dawn, the chickens were already scratching in the dirt. As Adonis fastened Vasso to his chain, the white rooster on the coop roof stretched its throat and crowed.

Between the house wall and a patch of flourishing thistles, Adonis rocked his old Vespa from its stand. Sliding the key into the ignition, he free-wheeled down the short track to the road, where, steering carefully around the potholes, he fired the engine.

In the town square, no one was open for business. Above the grocer’s shop, a light shone behind drawn curtains; the green cross over the pharmacy was lit, though the windows behind their iron grilles were dark. The shutters at the kafenion were barred and the door was closed, but someone was there, waiting to be served: at a pavement table sat a stranger.

Adonis, riding by, stared at the man – a big man, perhaps even fat, whose curly, greying hair was a little too long, and whose glasses gave him an air of academia. Beneath a beige trench-coat, he wore a suit without a tie; beside him lay a holdall of green leather. In Eva’s uncomfortable chair he seemed relaxed, drawing on a freshly lit cigarette, one foot crossed over the other; and it was the stranger’s feet that drew Adonis’s eyes. The fat man was

wearing tennis shoes – old-fashioned, canvas shoes, pristinely white.

Outside the pharmacy, red-painted barriers surrounded mounds of rubble and a hole in the road. Swerving to avoid the workings, Adonis switched on his indicator to signal left.

Making the turn towards the mountains, he glanced back at the stranger, who smiled as if Adonis were an old friend and raised his hand in greeting.

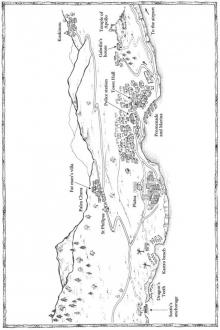

As the old Vespa laboured on towards St Paraskevi’s, the morning’s first sunlight broke the line between sea and sky. Away down the hillsides, beyond the cultivated fields of the plain, the coast road followed the line of the beach as far as the port, then disappeared amongst the streets and houses of the town. The ascent was long, increased by twists and loops in the mountain road, and lacking power in his small engine, Adonis leaned forward over the scooter’s handlebars in the hope of persuading it to higher speed; but his progress remained slow, and as he reached the right-hand bend where the weather-worn sign pointed the way to the chapel, the bell of Holy Trinity far below was already striking seven.

The unpaved track was rough, scattered with loose stones and rutted by trucks spinning their wheels in the mud of a wet winter; but the incline was gentle, and the long grasses which flourished on the slopes were coloured with the flowers of spring: powder-blue blooms of wild chicory, tall hollyhocks and purple lupins, fresh white margaritas.

The grazing where Adonis kept his flock lay beyond St Paraskevi’s, but as the little church came into view, he slowed the scooter to a walking pace. Beneath a conical roof, the round and ancient walls were no taller than a man, the whitewashed courtyard walls a few stones higher. Above the arch of the courtyard gate hung a single bell, its rope tied on a rusting, cast-iron hook.

Adonis made frequent promises to his mother to take the time each day to light the chapel lamps, though often – like today – he forgot matches. Those in the chapel were damp, their pink tips soft as chalk when they were struck.

The Bull of Mithros

The Bull of Mithros The Feast of Artemis (Mysteries of/Greek Detective 7)

The Feast of Artemis (Mysteries of/Greek Detective 7) The Taint of Midas

The Taint of Midas The Doctor of Thessaly

The Doctor of Thessaly The Whispers of Nemesis

The Whispers of Nemesis The Messenger of Athens

The Messenger of Athens