- Home

- Anne Zouroudi

The Feast of Artemis (Mysteries of/Greek Detective 7)

The Feast of Artemis (Mysteries of/Greek Detective 7) Read online

For Leo

‘Eat slowly; only men in rags

and gluttons old in sin

Mistake themselves for carpet-bags

And tumble victuals in.’

Sir Walter Raleigh,

‘Instructions to His Son’, 1632

Contents

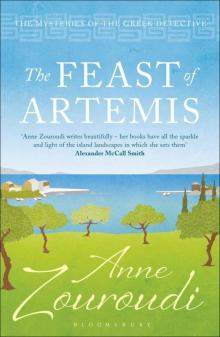

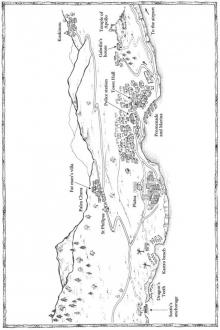

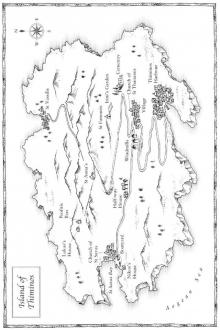

Map

Dramatis Personae

Glossary of Greek Language

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

A Note on the Author

By the Same Author

Also Available by Anne Zouroudi

Map

Dramatis Personae

Hermes Diaktoros, the fat man – an investigator

Dino – Hermes’s half-brother

Donatos Papayiannis – an olive farmer

Tasia Papayiannis – Donatos’s wife

Sakis Papayiannis – Donatos’s son

Amara Papayiannis – Sakis’s wife

Marianna Kapsis – a rival olive farmer

Dmitris Kapsis – Marianna’s step-grandson

Renzo Rapetti – an ice-cream seller

Lefteris Boukalas – a hotelier

Stavroula Boukalas – Lefteris’s wife

Tomas – Stavroula’s father

Katya – Stavroula’s aunt

Meni Gavala – a vintner

Esmerelda Dimas – a newspaper editor

Spiros Zysis – an olive-oil wholesaler

Miltiadis Sloukas – a tailor

Dora – owner of a kebab shop, a widow

Xavier – Dora’s son, a self-styled activist

Dr Fitanidis – a doctor at Neochori hospital

Arethusa – a waitress in Neochori

Takis Kapsis – a butcher

Glossary of Greek Language

amessos – immediately, at once

anthotyros – a goat or sheep’s cheese, often eaten with honey and fruit

baklava – pastry made with chopped nuts and syrup

bourekakia – pastry-wrapped savouries

chairo poli – delighted to meet you (formal greeting)

doxa to Theo – thanks be to God

filé – friend

fraskomilo – mountain sage, often used to make tea

galaktoboureko – pastry filled with semolina custard

glyfoni – apple mint, also used for tea

graviera – a hard cheese used for grating

gyros – a kebab: grilled meat etc. wrapped in pita

kafebriko – a long-handled pot used for Greek coffee

kakomira – poor thing

kalé – popular and familiar form of address

kali mera (sas) – good morning, good day (polite/plural)

kali nichta – good night

kali spera – good evening

kalo mezimeri – good afternoon

kalos ton/tou/tous; kalos irthate – welcome

kamari mou – term of affection, lit. my pride, my son

kataifa – nut-filled pastry made with shredded dough

kefalotyri – hard sheep’s milk cheese

keftedes – fried savouries of meat, vegetables, cheese or fish

kleftiko – Lit. ‘stolen meat’. The origins of the dish lie with sheep-rustlers, who baked stolen animals in covered pits to prevent smoke giving away the thieves’ location.

kokoras – cockerel

koproskila – vehement term of abuse

kori mou – my daughter

koritsia – girls

koukla/koukles – beauties, pretty girls (lit. dolls)

kyria (kyries) – Madam, Mrs (plural: ladies)

kyrie – Sir, Mr

malaka/es – common insult or term of abuse (singular/plural)

malista – certainly

manka – a not-quite gentleman or spiv

mikre – little one

mori! – exclamation of surprise

mou – my

panayia mou – by the Virgin

pappou – grandpa

pedia – people, everybody (lit. children)

periptero – kiosk selling cold drinks, newspapers, cigarettes etc.

poustis/es – slang term for homosexual (singular/plural)

salone – living room

santouri – stringed musical instrument made with mallets

skordalia – garlic sauce usually made with bread or mashed potatoes

souvlaki/a – skewers of grilled pork, lamb or chicken (singular/plural)

taramasalata – dip made from fish roe and olive oil

thea – aunt

theé mou – my God

theié – uncle, often used as a term of respect to an older man

toumba – children’s game of tag

tzatziki – dip made from yogurt and garlic

yammas – cheers, good health

yassou/yassas – hello or goodbye (singular/plural or polite form)

yiayia – grandma

yie mou – my son

One

The fire-pits lay across the hillside, graves of the unmourned beneath bare heaps of the dirt which had filled them. The pine planks acting as their markers bore rough-painted family names, and the menfolk were ready to play sextons, shovels close at hand for when the call came.

The Papayiannis men checked their watches, counting down the remaining minutes as they passed round the ouzo bottle, drinking to the win they were confident would be theirs, trading bawdy jokes and laughing lecherously and loud. To left and right the opposition waited, backs to their rivals and segregated in their clans.

Below them, the church’s domes and arches straddled age-mellowed stone walls, where a bronze sundial was mounted on a marble plaque. Smart in the suit he had worn on his wedding day twenty-three years before, the mayor scrutinised the sundial, and when he judged the shadow of its arm to be touching noon, he gave a signal to the bellringer, who began a spirited tolling of the bell. The mayor ran to the courtyard gateway, and with his hands around his mouth to carry his voice, shouted up to the expectant men on the hillside, ‘Pedia! It’s time!’

At all the pits, the men began to dig, throwing aside the dry topsoil, working fast to uncover what lay beneath.

But at the Papayiannis pit, the dry soil was only a shallow covering, quickly removed to reveal dark, damp earth beneath.

Sakis Papayiannis was first to notice the change. He held up his hand, and called the digging to a halt.

In surprise, his relatives pulled their shovels from the dirt.

‘Are you crazy?’ asked a cousin, in annoyance. ‘We won’t win by sitting on our arses.’

Sakis crouched down, and touched the newly exposed soil. Away to the right, the Kapsis men broke through the earth seal, and the fire-pit released trapped smoke and steam made mouth-watering with roast meat and herbs. They set their spades aside, and two of them pulled on leather gauntlets to dig with their hands. A boy ran out from amongst them, shouting as he reached the church, ‘We’re first! We’re first!’

‘That smells good,’ said an elderly Papayiannis uncle, sniffing at a drift of Kapsis smoke. ‘I heard Takis reckons he’s sure of a win this year, and he’s been working on his seasonings since Easter. I suppose it

won’t hurt that he’s a butcher. He’s bound to have the best animal to begin with.’

‘Being a butcher didn’t help him last year,’ countered his great-nephew. ‘And the judges are men of plain tastes. Good meat, well cooked, always does it.’

‘What the hell’s the problem?’ demanded the cousin, who had drunk plenty of the ouzo and swayed slightly as he stood, as though the hill’s gradient were throwing him off-balance. ‘Let’s dig, malaka. They’re halfway down already, and we’ve hardly started.’

The other clans were finishing their spadework, and the air was full of tantalising smoke. Sakis placed his palm on the top of the fire-pit. The soil was cold. Putting his hand to his nose, he sniffed, and grimaced.

The mayor was coming up the hillside.

‘Dig further,’ said Sakis to his nephew, a strong lad in his Sunday-best denim jacket. The boy quickly shifted another half-metre of dirt, working up a sweat which broadcast his cheap cologne. The deeper he went, the darker and damper the soil.

The nephew stopped digging.

‘Something stinks,’ he said, pulling a face. ‘Have the cats been at this?’

‘Big cats, maybe,’ said Sakis. He glowered towards the Kapsis clan. Now well in the lead, they were hauling hot stones from their pit, calling to each other to take care as they tossed them away into the long grass.

A lanky youth caught Sakis watching, and held up a bottle of beer in a mock toast.

‘You slackers should get a move on!’ he shouted, to laughter from those around him. ‘The people want to eat today!’

The cousin took several unsteady steps in his direction.

‘Dmitris Kapsis,’ he said. ‘That little prick wants teaching some respect. I’ll soon sort him out.’

‘Leave it. He isn’t worth it,’ said Sakis.

‘He’s right, though,’ said the nephew. ‘We’re falling way behind.’

‘Yes, for God’s sake, Sakis, let’s get on,’ said the cousin. ‘I’ve got a raging thirst, and there’s nothing left to drink.’

‘We’re wasting our time,’ said Sakis. ‘There’ll be nothing to eat from this pit. No kleftiko today.’

The men around him stared.

‘What do you mean?’ asked one. ‘Why not?’

‘Because it’s cold,’ said Sakis, bitterly. ‘The pit’s cold.’

The mayor reached the Kapsis’s pit, and the Kapsis men offered him warm greetings.

‘You’ve come at the right time,’ one told him. ‘We’re just about ready to go.’

Their pit smoked and steamed like the entrance to hell. They raised a bier of chicken-wire from its wood-ash bed, and reverently laid the bundle it carried on the grass. With a hunting-knife, one of the Kapsis elders sliced through a charred, ash-dulled foil shroud, and with his fingers twitching away from the heat, peeled it back. Under the foil, he cut the nylon rope binding a brown-stained cotton sheet. The Kapsis men and the mayor all gathered round, and as the last covering was removed, they looked down on a roasted lamb, its skin glistening with its fats, flesh falling from its bones. The head was reduced to a skull with grimacing teeth, the footless shanks were scorched red; and though only the charred, twiggy remains of mountain oregano and thyme poked through the haphazard string stitching of the belly cavity, a fragrant steam affirmed that all the herbs’ sweet essences had melded with the meat.

The Kapsis men were jubilant.

‘It’ll be hard to beat,’ said one.

‘Carve a slice, and let’s try it,’ urged another. ‘Let the mayor have the first taste.’

But the majority shouted him down.

‘It goes to the judges whole,’ they said. ‘Cut into it now, and we’ll lose all the juices.’

‘I’m happy to wait till the judging,’ said the mayor. ‘Congratulations, gentlemen. It’s a triumph.’

The Kapsis lamb was carried down the hillside, whilst the mayor moved on from pit to pit. By the time he reached the Papayiannis men, they had dug down to the stones which covered their carcass. As the mayor approached, they fell silent.

‘Gentlemen,’ said the mayor, nodding to the group. He looked down into the cold pit. ‘How’s it going?’

‘You see this?’ asked Sakis. He picked up a handful of earth and held it out to the mayor.

The mayor was puzzled.

‘What am I looking at?’

‘Touch it,’ said Sakis, and with reluctance, the mayor did so. ‘It’s cold. And wet. And you smell it.’ He held the dirt to the mayor’s nose. The mayor sniffed, and pulled a face. ‘And look.’

Sakis reached down into the pit and with his bare hand pulled out a stone, which in the other pits would still be too hot to touch. He offered it to the mayor, who took it reluctantly. The stone was no warmer than blood-heat.

Sakis hauled out more stones, uncovering the Papayiannis lamb. He touched its wrappings, and shook his head.

‘Let’s get it out,’ he said.

The men lifted out the lamb on its bier, and laid it on the excavated heap of dirt. In the pit bottom were more lukewarm stones, and under them, a grey mess of wet wood-ash. When the carcass was cut free of its bindings, the flesh was raw.

The mayor clapped Sakis on the shoulder.

‘Your pit wasn’t hot enough,’ he said. ‘Or the heat died too fast. It happens, sometimes.’

Sakis spread his arms, and beckoned his relatives closer.

‘You see these men?’ he asked the mayor, in a voice which, though reasonable, carried an undertone of anger at the affront. ‘These men here, and I myself – we’ve been preparing kleftiko for generations. Our fire-pits burn hotter than Hades, and our pit didn’t die, it was doused. Someone poured water on it, a lot of water. And worse than that.’ He sniffed at his hand and offered it again to the mayor, who turned his face away. ‘Somebody pissed on it.’

The mayor laughed, nervously.

‘You don’t know that,’ he said. ‘Cats, you know, if they smell the meat . . .’

‘Are you suggesting,’ asked Sakis, ‘that I don’t know the difference between cat piss and human piss? We’ve been sabotaged. This is an act of malice. And we all know where to look for the culprits.’ He pointed towards the Kapsis’s, where several men were filling in the pit, and the cousin spat in their direction. ‘They should be disqualified.’

‘How can I disqualify them?’ asked the mayor. ‘You don’t know for certain that it was them.’

‘But you concede there’s been sabotage?’

The mayor hesitated.

‘I have to say it does seem that way,’ he said. ‘But as to who it was . . .’

‘We know who it was. And if you won’t do anything, I will.’

‘Please, Sakis,’ said the mayor. ‘Don’t make trouble. Don’t spoil the day. I know you as a reasonable man, and the time to settle scores isn’t now.’

But Sakis yelled across to the Kapsis’s.

‘You cowardly bastards! Is that how men behave, pouring water on a fire in the night? Pissing on our family’s food?’

The Kapsis clan jeered.

‘No fire in your pit, and no fire in your balls!’ they shouted back. ‘Don’t worry, we’ve got enough meat to spare for your women!’

They thrust their hips raunchily, and gestured at their genitalia in outrageous insults.

The taunted Papayiannis men watched uneasily, expecting Sakis to give the word to take them on.

But Sakis was striding away down the hillside.

‘Where the hell are you going?’ his cousin called after him.

‘I’m going to tell the old man,’ Sakis shouted over his shoulder. ‘I’m going to tell Papa what those bastards have done.’

It was the day for honouring the Archangel Michael, and in the courtyard of the church, preparations for the festival were almost complete. Blue and white bunting fluttered between the trees; the soulful ring of santouri music played through tinny speakers rigged in the branches, and all around was the rich savour of food: apples baked

with cinnamon, chicken braised with garlic, fried fish, grilled cheese and slow-simmered beef. Boys playing toumba ran in mad circles, ducking under laden tables where their mothers laid out bread and baklava; girls licked sweet cream from sticky cakes, and wiped chocolatey fingers on their party dresses. Beyond the courtyard gate, a gypsy hawker smoked in moody silence, a cloud of gaudy balloons bobbing over his head.

Sakis pushed through the crowd, ignoring anyone who spoke to him, making no apologies to those he jostled, until he reached the overhanging olive tree where the women of the family were gathered. His wife, Amara, was making space on the table for a pan of lemon potatoes; his mother and mother-in-law were debating where the galaktoboureko was best placed. Amongst the women, his father, Donatos, sat in his wheelchair, wearing his favourite fedora, his walking canes resting against the chair’s frame. He was sharpening a long-bladed knife on a whetstone, concentrating on the rhythm of his strokes.

Amara saw Sakis approaching, and alerted the others, who all looked at him expectantly. The table for the Papayiannis kleftiko was ready, with a sheet of clear polythene covering a white cloth, and plates, napkins and forks all laid out; at the corner of the table was a silver trophy decorated with ribbons, inscribed for the previous year with the Papayiannis name.

Donatos drew the knife-blade lightly across his thumb-pad. A red line appeared on the skin. Satisfied, he leaned forward in his chair, and laid the knife alongside the trophy.

Across the courtyard, at the Kapsis tables, the first slices of roast meat had been carved. Through the gate, another clan’s menfolk carried in their lamb, holding it over their heads to show off its quality. A cheer went up from their family.

‘Here he is,’ said Amara, brightly, as Sakis reached them. ‘Here’s the man of the moment!’

‘How is it, son?’ asked Donatos. The small act of leaning forward left him wheezing, and with his fast and shallow breathing, his ruddy face was growing more florid. ‘Is it good?’

Sakis’s mother, Tasia, wiped her hands on her apron.

‘We’re all ready for you,’ she said. ‘Where is it?’

But Amara saw the fury in Sakis’s face.

The Bull of Mithros

The Bull of Mithros The Feast of Artemis (Mysteries of/Greek Detective 7)

The Feast of Artemis (Mysteries of/Greek Detective 7) The Taint of Midas

The Taint of Midas The Doctor of Thessaly

The Doctor of Thessaly The Whispers of Nemesis

The Whispers of Nemesis The Messenger of Athens

The Messenger of Athens