- Home

- Anne Zouroudi

The Feast of Artemis (Mysteries of/Greek Detective 7) Page 2

The Feast of Artemis (Mysteries of/Greek Detective 7) Read online

Page 2

‘What’s wrong?’ she asked him. ‘What’s going on?’

‘There’s no kleftiko,’ he said, angrily. ‘Our pit was sabotaged.’

Behind him, his relatives shouted agreement and support. The drunken cousin forced himself forward, and started on his version of the tale, but the ouzo made him rambling and repetitive.

‘Let me tell it,’ Sakis insisted. At the neighbouring tables, the women fell into silence, listening as they were laying out their food. ‘Those bastards . . .’ He stabbed a finger towards the Kapsis’s, where a loud toast was being drunk to begin the feast. ‘Koproskila! They doused our pit! And if that wasn’t enough, they pissed all over it!’

Shocked, the women began to ask questions, raising their voices over each other to be heard. Donatos grabbed his canes, and with his free hand, began to raise himself from his wheelchair.

‘Donatos, sit down!’ said Tasia. ‘Get back in your chair, or you’ll fall.’

‘For Christ’s sake, stop your nagging, woman!’ said Donatos. ‘I can manage perfectly well on my own two legs.’ Out of the chair, he leaned heavily on his canes. ‘Sakis, yie mou, let’s go.’

‘But where are you going?’ asked Amara. ‘Sakis, don’t you go losing your temper!’

‘Don’t you let your father go looking for trouble, Sakis!’ said Tasia. ‘His heart’s not strong enough to cope with any trouble!’

‘There won’t be any trouble,’ said Donatos. ‘But this has gone on too long. I’m handing this over to the law. We’re going to find a policeman.’

Donatos walked painfully with his canes, halting every few steps to catch his breath, Sakis following close behind, both men giving only curt responses to those who offered greetings. Beyond the courtyard gate, outside the church precincts where they were permitted to smoke, a group of men was gathered, watching people make their way up to the festival from the town. The narrow road below was lined with cars, trucks and vans. Amongst them was a police car.

Donatos was badly out of breath. Against a wall was a broken-backed bench, where three plump girls in frothy dresses dipped into bags of candy floss.

Donatos stopped in front of them, and raised one of his canes.

‘Shoo, pretty ones,’ he said. ‘Shoo, and let an old man sit down.’

Silently, the girls slipped down from the bench, and sloped scowling away. Donatos sat down heavily, closed his eyes and leaned forward almost on to his thighs, as if trying to bring oxygen to his head. For a few moments, he was still. Then he sat back, and looked up at Sakis, who was watching his father with concern.

‘Are you still here?’ asked Donatos. ‘Go and tell them to come up here. Tell them I want to speak to them.’

‘I’ll do my best,’ said Sakis. ‘But what if they won’t come? Maybe it would be better if we went to them.’

‘They’ll come. Just tell them who I am,’ said his father.

Sakis walked away, towards the police car. Donatos pulled a waxed bag from his pocket. He propped his canes against his knee, and peered into the bag, at several golden pieces of almond praline – whole almonds encased in brittle caramel. He searched for a piece the right size, but not finding one, he broke a large piece in half, and put one of the halves in his mouth. He sucked and savoured the hard sweetness, then crunched it between his teeth, breaking into the nutty smoothness of the almonds as he chewed. And very briefly, his face relaxed into a smile.

The police officer at the wheel of the car was chewing gum, his jaw moving like a goat’s, his tongue clicking lightly with every clamping of his teeth. His colleague – who was barely more than a boy – was dipping into a large bag of Cheetos. As Sakis approached, the driver watched him in the side-view mirror.

‘Yassas,’ said Sakis, when he reached the driver’s open window.

The driver wished him the same; when he spoke, the glob of gum showed in his mouth. He had recently been to the barber’s; the line of his short haircut was immaculate, the nape of his neck shaved smooth.

‘Can I trouble you to come and talk to my father?’ asked Sakis.

‘He’ll have to come to us,’ said the driver. ‘We’re not allowed to leave the vehicle, in case of an emergency. We have to stay close to the radio.’

‘But he’s too infirm to come down here. He wants to make a complaint. We both want to make a complaint.’

‘He’ll be leaving the church eventually, so why not now?’ asked the driver. ‘Or is he planning to stay up there all night?’

‘If he comes down, he won’t easily get back up again,’ said Sakis. ‘We used a wheelchair to get him up there, and it took the best part of half an hour. My father is Donatos Papayiannis. His cousin was one of your chief inspectors, for many years.’

The policemen looked at each other, and pulled faces to confirm Donatos’s name meant nothing. The younger man reached into the bag for another Cheeto. He put it in his mouth, and sucked staining orange powder from his fingers.

‘I don’t know him,’ said the driver. ‘What’s your complaint?’

‘Sabotage,’ said Sakis. ‘We had a pit, a kleftiko pit, and someone doused it.’

The driver’s eyebrows lifted a touch. His colleague smirked and looked away, as if something outside the car had become suddenly interesting.

‘How did they sabotage it?’ asked the driver, tightening his jaw to stop a smile breaking through.

‘With water,’ said Sakis. ‘And they urinated on it.’

The driver’s eyebrows moved higher. His colleague snickered, and tried to disguise it as a cough.

‘I have to say,’ said the driver, ‘that pouring water isn’t a criminal offence. Did it cause any damage?’

‘Of course it did!’ said Sakis. ‘It doused the fire-pit! Instead of roast lamb, I’ve got a raw carcass!’

‘It’s still a carcass, though,’ said the driver. ‘Relight your fire, and there’s no problem, surely?’

‘With their piss on it?’

The driver looked uncomfortable.

‘I know who did it,’ said Sakis. ‘They’re up there in the church, now.’

‘Did you see them?’

‘No.’

‘Do you have any witnesses?’

‘No.’

The driver sat up in his seat.

‘Tell you what I’d do, in your shoes,’ he said. ‘If you think you know who did it, go and have a quiet word. But it sounds like a prank to me. I’d try and see the funny side, if I were you. There’s always next year.’

Sakis fixed the officer with a glare.

‘Are you new here?’ he asked. ‘New in Dendra?’

‘I’ve been here a couple of months,’ said the driver. ‘What’s that to do with anything?’

‘Never mind,’ said Sakis, walking away. ‘Forget I mentioned it. Like you said, I’d do better to sort it out myself.’

Two

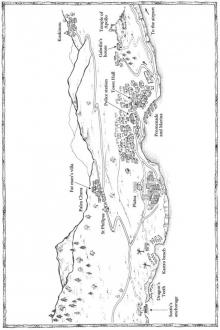

In ages past, the ancient citadel was a formidable defence against enemies from the sea. The outer walls of great stone blocks had survived intact, and in many places had kept their jagged battlements; but the watchtowers were roofless and disintegrating, and little was left of the buildings where soldiers had eaten and slept but their outlines in rubble, with weeds and grasses growing where there had once been floors.

The ascent to the citadel was steep, and missing cobbles and loose gravel made the path hazardous, but the man approaching the stronghold moved with confidence, and at a good pace for one considerably overweight. Passing through an arched gateway, he wandered for a while amongst the traces of old rooms. Finding an open well, he tossed in a coin, counting the seconds of its fall to measure the depth, but the coin’s chink as it bounced off the shaft’s rocky protrusions only faded away, and the sound of its hitting bottom was too distant to be heard.

The ruins seemed desolate, and lonely, as if those who had stood guard in the watchtowers and challenged strangers at the gates were still missed. The fat man climbed up to the wall-walk behind the ramparts, and gazed out over th

e land the citadel had once protected. The countryside was becoming green with the autumn rain; acres of silver-leaved olive trees covered gently sloping hills. Some way off lay a town, and round about were smallholdings and farms, all connected by a sparse network of roads. To the north, there were high mountains, and to the south, in the distance, the sea.

The wind, high up, was strong, its gusts bending the long grasses and tousling the fat man’s greying curls, which were overdue the attention of a barber. His owlish glasses gave him an air of academia; under his raincoat, his bark-brown suit was subtly sheened, and expertly tailored to flatter his generous stomach. His pale green polo shirt had a crocodile on the chest, and on his feet he wore white shoes, old-fashioned canvas shoes of the type once used for tennis; in his hand was a sportsman’s hold-all in black leather, painted in gold with the emblem of a rising sun.

Overhead, a circling eagle cried. The fat man raised his coat collar against the wind, and left the ramparts by a stairway of rough steps, where the mortar between the stones had long ago been washed away. The steps led to a once substantial building; the lines of its foundations were distinct, and a single cornerstone was still in place, a large block left behind when the walling stone had been pilfered for newer buildings. Towards this ruin’s eastern wall, almost buried and lost to the dirt and weeds, was an altar.

The fat man crouched, and felt the faint grooves which were all that remained of the altar-front inscriptions. He traced a ‘D’, and an ‘I’, a ‘Y’ and a final ‘S’ – enough to identify the name of Dionysus, ancient god of the vines – and, seeming pleased with this discovery, he patted the stones, and rising to his feet, returned to the ramparts.

As he leaned on the battlements, he saw a plume of smoke rise behind the town; minutes later, a second plume appeared, followed by a third, and a fourth. The fat man watched until the smoke dispersed, carried away by the wind. Then he left his post on the ramparts, and made his way back down the path to the road far below.

In the car park below the citadel was a single vehicle – a vintage sports car with a stretched bonnet and bold tail-fins, and the grime of the road covering its white paint. The fat man placed his hold-all in the passenger footwell and slipped in behind the wheel, where the seat was set well back to accommodate his bulk. When he turned the ignition, the engine gave a roar, and blew an oily black cloud from the exhaust; but the fat man seemed unperturbed, and resting his arm on the central console, he put the car into gear.

He headed in the direction of the smoke he had seen from the ramparts, following the road in its broad sweep towards the coast. On the radio, reception was poor, and the rich voice of Notis Sfakianakis faded in and out with the curves in the road. There was little traffic: a few freight trucks, a tractor and a number of cars spattered with rural mud, which though battered and scratched, tore past the fat man, who motored at a steady pace, admiring the views. Within a few kilometres, a sign showed an approaching junction and a road joining from the left; and since that was the direction of the smoke, the fat man flicked on his indicator, and – even though there was no other traffic in sight – moved cautiously to the centre of the road to execute a careful turn.

The road he found himself on was less straightforward in its intentions than the highway he had left, first following the path of a river, then winding in looping bends. He passed a run-down smallholding, where a mange-tormented dog began a frenzied barking, and thin sheep foraged around the tree roots in a lemon orchard. A roadside booth advertised oranges, though there were neither oranges, nor salesman; but a little further on was another makeshift stall, a table and a shabby kitchen dresser sheltered with a tarpaulin. Here, under a sign reading ‘Local Produce’, sat two men, a bottle of red wine on the ground between them, each with a glass in his hand. One seemed obviously a farmer, dressed in a flannel shirt and jeans and with a weather-leathered face; but the other made him an unlikely companion, having the look of an ageing hippy.

The fat man cast an eye over the pair and allowed himself a smile; the two seemed set there for the duration. But as he motored by, the hippy leaped to his feet, and glass still in hand, chased after the fat man a few paces, then stood in the road, waving his free hand in the air.

‘Stop!’

The fat man heard the shout, and glanced in his rear-view mirror. Seeing the hippy there waving, he slammed on his brakes; and as the hippy began to run slowly towards the car, the fat man reversed in his direction.

He stopped alongside the hippy, who was somewhat glazed and smiling. His yellow T-shirt was splashed with wine spilled as he ran; below his tan cord trousers, his sandalled feet were dusty, and his toenails much too long. His neglected beard grew to his chest, his hair down to his shoulders though his high forehead was bald. Beneath unkempt eyebrows, his eyes were very blue. The smell of alcohol seeped through his pores and was on his breath; the flaking skin on his dry lips was black from the wine.

He grinned, showing his wine-stained teeth, and swaying slightly, held up his glass in a salute.

‘Yassou, Dino,’ said the fat man.

‘I thought it was you,’ said Dino. ‘How’s life been treating you, brother?’

In the cramped space behind the Kapsis family’s tables, the women were uncovering more food.

‘What have you brought, kalé?’ one asked her sister.

‘I made my aubergine pilaf.’ She lifted the cloth from an heirloom tapsi – a vast brass-handled copper pan, much dented from knocks on stone ovens – to show a mound of rice flavoured with cloves and bay, mixed with aubergines, almonds and currants. ‘And a loaf of my cheese bread.’ She unrolled the loaf from a white napkin, and laid the bread towards the front of the table where it could be admired. Scents of yeast, warm feta and oregano rose from its crust. ‘What about you?’

‘I brought sausages with green beans. They’re Takis’s best.’ The first sister pointed to a cast-iron pan. The sausages were pork, minced with the pig’s liver and its kidneys, well seasoned with paprika and parsley, stewed with the beans in a piquant tomato sauce. ‘And I made revani, Mama’s recipe.’ On a blue plate, her semolina cake sat in a pool of its own cinnamon-spiced syrup. A slice was missing from the end. ‘I thought I should try it, in case I hadn’t used enough sugar, but I worried for nothing.’ She turned to a pretty girl busy beside them. ‘Where’s Marianna?’ she asked. ‘Where’s your aunt?’

The girl pointed to a corner of the courtyard, where several wine barrels had been mounted on trestles, and a gaggle of grandmothers bickered over an arrangement of carafes and cups. Close by, a tall and ample woman talked with another much more petite, until the petite woman excused herself, and bent to make adjustments to the wine taps. The tall woman began to make her way towards the Kapsis tables, faltering in patent heels.

‘Here she comes,’ said the pretty girl.

‘About time,’ muttered one sister to the other.

From across the courtyard, Amara Papayiannis watched Takis Kapsis carve the kleftiko, sweating from the heat of the roast and the alcohol he had drunk. The clan’s women were gathered round him, holding out platters for him to fill.

‘Look at them,’ said Amara. ‘Carrying on as if nothing happened. I’m going to tell them what I think.’

‘Leave it, kalé,’ said her mother. ‘The men will sort it out.’

‘What will they do?’ asked Amara. ‘Bleating to the police will help nothing.’

‘It’s not for us to take it on ourselves. We’ve plenty of food anyway, without the lamb.’

‘You’d let them get away with it, but I won’t. Enough is enough, Mama. Sakis is so upset, and this kind of stress is bad for Donatos’s heart. Sometimes we have to stand up for our self-respect. For our family. What does the bible say? An eye for an eye, and a life for a life.’

‘That’s not what Christ said, though, is it?’ Her mother made a triple cross over her heart. ‘We should turn the other cheek, that’s what he’d say. Look, there’s Papa Kostas. You can ask him.

He’ll tell you what’s right. Papa! Papa!’

She picked up a dish of baked figs, and held it up whilst beckoning to the priest, who was moving from table to table, accepting tastes and morsels from the housewives of his congregation.

‘Kyries, kali mera sas,’ he said. For his age, he was a good-looking man. Amara’s mother went a little pink.

‘I was wondering if you’d try one of these,’ she said, and offered him the plate.

The priest’s hand hovered over the honeyed figs, until he chose the plumpest. He bit into it, and closed his eyes in pleasure. Amara’s mother waited for his verdict.

‘Marvellous,’ said the priest, smiling broadly.

‘I wasn’t sure,’ said Amara’s mother. ‘I used pistachios with the apricots in the stuffing, and I wasn’t sure it would work. Usually I use walnuts, but I thought this year I’d be more daring.’

‘Sometimes it pays to be daring,’ said the priest, and gave her a wink. ‘These are a delight, a triumph!’

‘Have another,’ she said. ‘Please.’

He hesitated only for a moment.

‘They really are very good,’ he said, and bit into the soft flesh.

‘Whilst you’re here, Papa,’ said Amara’s mother, ‘can you advise my daughter? She has a question she’d like to ask you, haven’t you, Amara?’

She looked round for Amara, but Amara wasn’t there.

Marianna was a little out of breath; the tray she was carrying was heavy. Two small girls followed behind, both struggling with wicker baskets which knocked their shins.

‘Koritsia, koritsia,’ she said. ‘I’m late, I’m late. Have you been coping without me?’

‘We’ve coped,’ said one of the sisters, shortly. She looked Marianna up and down. The sister’s hair was grey, and cut matronly short; she and Marianna were the same age, but Marianna’s curled hair was bleached a nicotine blonde. The sister was too modest to think of make-up, but Marianna wore coral lipstick, with rouged cheekbones and peachy powder on her nose. ‘Are those more new shoes? I’d never be able to walk in anything like that.’

The Bull of Mithros

The Bull of Mithros The Feast of Artemis (Mysteries of/Greek Detective 7)

The Feast of Artemis (Mysteries of/Greek Detective 7) The Taint of Midas

The Taint of Midas The Doctor of Thessaly

The Doctor of Thessaly The Whispers of Nemesis

The Whispers of Nemesis The Messenger of Athens

The Messenger of Athens