- Home

- Anne Zouroudi

The Whispers of Nemesis

The Whispers of Nemesis Read online

The Whispers of Nemesis

Anne Zouroudi

For my mother

His end was recorded somewhere and then lost;

Or perhaps History passed it by,

And with good reason, a thing as trivial

as that she didn’t deign to record.

C. P. Cavafy, ‘Orophernes’

Contents

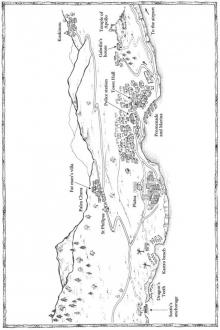

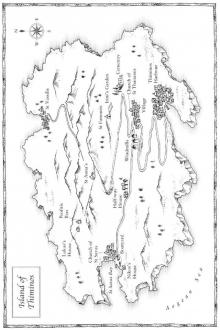

Map

Exhumation

One

Four Years Previously

Two

Three

Four

Five

Pre-exhumation

Six

Post-exhumation

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Death

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Reburial

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-one

Twenty-two

In Memoriam

Epilogue

Glossary

Dramatis Personae

A Note on the Author

By the Same Author

Exhumation

The rite of exhumation . . . is the last important rite that must be performed individually for a particular dead person by his surviving kin. The relationship between the deceased and his relatives is for the most part ended at the exhumation. After this the obligations of the living to the deceased are carried out collectively on occasions that serve to honour all the dead.

Loring M. Danforth, The Death Rituals of Rural Greece

One

All uniformed in worn, black coats, all their lined and bitter faces bound in black headscarves, the old women gathered at the graveside. Under the broad-spreading branches of the oak which shaded the plot, the components of the grave’s furniture had been dismantled. The headstone’s front face leaned against the cemetery wall, hiding the inscription and the glassed-in photograph of the poet as a smiling young man; the candle-lamps (which had not often been lit) and the flower-vase (which had, in the main, held artificial flowers) lay discarded on a neighbouring tomb. In the years following the burial, the once-white marble kerbstones had rarely been scrubbed, and were discoloured with algae and yellow lichens. The old women took in the stone’s neglected state, and cast their offended eyes up to the heavens.

The bell of Vrisi’s village church began to toll. In these northerly mountains, there was no hope yet of spring, and the wind which flapped the men’s trouser-legs and stirred the evergreen branches was raw; the sky was an ashen veil, cast over the day’s end.

‘There was a woman over in Loutro they buried too close to a tree,’ muttered one crone into the cold-reddened ear of another, inclining her head towards the oak, and to the bare and stony ground where the coffin had been laid, four years before. On that occasion, the earth – freshly dug and mounded up for the interment – was the lively brown of spring sowing; now that same earth, settled and sunk, was cracked and pale. ‘Its roots were poking through the poor soul’s eyes! Bound by that tree, she was, until they cut her free. And this tree will have claimed him, just the same!’

The sexton leaned on his spade, impatient for his cue to break the ground, but the old women were still busy with their preparations, checking the necessities for the ritual: holy basil for blessing, and red wine to wash the bones; white kerchiefs to wrap them, and a metal box to hold them in their final place of rest.

A little apart, in fashionable black jackets and court shoes, two younger women stood, one of an age to be parent to the other. Ready to proceed at last, the old women hustled them closer to the graveside.

‘Come forward, kalé, come forward,’ they insisted. ‘It’s the faces of his close kin he’ll want to see, as he comes back to us.’

The poet’s sister and his daughter complied reluctantly, his sister encouraging her niece with an arm around her shoulder.

‘Courage, glika mou,’ said Frona. She hugged Leda close, and placed a kiss of comfort on her temple. ‘Courage, and it’ll soon be done.’

Leda wiped her nose on a cotton handkerchief, and turned her miserable face from her father’s grave. Behind the eager old women, Attis Danas drew on a slender cigar, and tried in vain to catch Frona’s eye. The widow Katerina – whose deceased husband had once been mayor and still bestowed on her some status, even years after his death – gave a signal to the sexton, who raised his spade, and brought down the blade with all his strength to break the grave’s hard earth. As he threw aside the first shovelful of stony soil, Katerina raised her voice in a lament, and the old women gathered around her began to wail. They moaned and shrieked to break all hearts, and the widow’s tears ran freely as she sang: of their grief at the poet’s final sight of daylight, and of their loss of him to the darkness once again; though the weight of the earth would be removed at last from his chest, his time with them was gone, and soon he would be lost to them for ever.

The sexton dug down deeper into the grave, where he was hindered, as anticipated, by roots of oak. The old women nudged each other, and made flamboyant crosses over their breasts. Frona put her hand up to her mouth, and bit a knuckle. Leda looked towards the cemetery gates. Attis wandered away along the paths between the tombs, struggling against the wind to relight the stub of his cigar.

‘That woman in Loutro,’ muttered the crone into the ear of the other. ‘She was the widow of a jealous man, whose tormented spirit possessed the tree to keep her bones out of the ossuary. Her being in there, with everyone else, was more than he could bear.’

‘Why did he object to that?’ asked the other. ‘If his own bones were in the ossuary, why didn’t he want her in there, with him?’

Her companion tapped her nose, and glanced around as if it mattered who was listening.

‘They said she’d had a lover, in her youth,’ she confided. ‘The spirit feared she might be put to rest near him, so it had the tree bind her bones, to keep them in the ground. Mori! It took an age to get her out. The roots were tough as rope, and woven all together, like a net. They had to fetch a hacksaw, and they cut for hours and hours. But the bones were white, I remember that. The bones were white, so she was blameless.’

‘I doubt his bones’ll be white,’ replied the other, pointing at the hole where the sexton worked. ‘We’ll know for certain the man he was, when he comes back to the light.’

A gust of wind blew cold. Under Frona’s arm, Leda shivered.

‘She feels her father’s spirit,’ whispered the women. ‘Her father knows we’re here.’

The sexton dug down, and down; the work was heavy, and sweat beaded his face, until he pulled off his dirty jacket and threw it on to the dismantled kerbstones. Katerina’s lamenting rose, fell and died away, rose, fell and died away; the women’s tears dried, and flowed.

When Attis returned to the gathering, the earth the sexton was shovelling was showing changes of colour, a vein of black within the paler soil.

The sexton stabbed his spade into the ground, and wiped the last sweat from his face.

‘Katerina!’ he called out. ‘Katerina, come down here, kalé! Come and take your turn!’

Katerina pulled on a pair of rubber gloves; the old women gave her a trowel, and handed her down into the hole as the sexton climbed out. They crowded round the grave, elbowing each other to get closer, their mourning role forgotten in their enthusiasm.

‘Find the skull first, mori!’ called one. ‘Make sure you bring out the skull first!’

‘Don’t break it!’ called another. ‘Fetch it out in one piece if you can!’

&nb

sp; Frona raised her face to the sky, and closed her eyes; Leda covered her mouth, as if she might be sick.

‘I can’t watch this,’ she said, shaking her head. ‘Please, aunt. Don’t make me.’

‘We must,’ said Frona, though her own doubt was clear. ‘A few minutes of courage, and all will be done. Hold my hand, and be strong.’

The widow squatted in the dirt, and scraped at the loosened earth with the edge of her trowel until the soil gave way to the first fragments of rotting wood.

‘I’ve got him,’ she said quietly, and made a cross over her breast. ‘Santos, kamari mou, come home!’

Under her hands, and with the leverage of the trowel, the softened remnants of the coffin lid were soon removed. Beneath, there was no hollow space, but the outline of the casket filled with dirt, which gave off an intense smell of organic matter, natural as the essence of earth distilled, without putridity, but heavy with fungal decay.

As the widow sifted through this darker, richer soil, the old women squabbled over where the head would be – Higher up, kalé, away from you, up here towards the wall – until the trowel rang out as it struck the first hard bone. Dropping the trowel, the widow covered her left hand with a white kerchief, and with her gloved right delved down into the pit.

‘I’ve got it!’ she said, at last.

‘She’s got it, she’s got it!’ they murmured.

‘It’s stuck,’ she said, a moment later.

‘The roots have him,’ they muttered. ‘The roots have him trapped!’

‘Wait!’

Holding on his priest’s hat against the wind, an anorak zipped over his robes, Papa Tomas hurried along the path towards the gathering, limping from his bad hip. As he pushed his way through, he greeted those he passed closest to by name, and marked those of whom he was especially fond with a touch, until – panting from his speedy walk up to the cemetery – he reached Frona and Leda.

‘Forgive me, forgive me,’ he said to Frona, pressing her free hand between his own. ‘That old clock of mine has stopped again! It’s unreliable, and I should throw it out, but we grow attached to things, don’t we, we grow attached. Leda, kori mou, have courage. We shall honour your father, and carry his bones to their final rest. How are we getting on?’ He released Frona’s hand, and looking down on the widow, wished her kali spera.

‘You’re just in time, Papa,’ said Katerina. ‘He’s here, beneath my fingers.’

A scrawny hand gripped Leda’s shoulder.

‘Don’t you worry, kalé,’ said an old woman, speaking low in Leda’s ear. ‘Your father was a good man, and his bones will be white, and clean.’

‘I have him!’ cried Katerina. ‘I have the skull!’

She pulled from the earth an object black with soil, and held it before her.

‘Pass it up,’ called one of the gathering, impatiently. ‘Pass it to his daughter, so she can wash him.’

But no one joined her in her demand. All were staring at the object in Katerina’s hand.

Bewildered, Frona turned to Papa Tomas.

‘Panayia mou,’ said Papa Tomas, and made several urgent crosses in the air.

Leda ran, and no one moved to stop her; she ran the path between the tombs, as far as the cemetery gates, where she kicked off her shoes, picked them up and ran on faster, down the lane between the snow-banks which still lay at the verges. The cement was cold and hard, and sharp stones pricked her feet; but in the exhilaration of running barefoot, her stricken face relaxed, and as she slowed down to a walk, the redness of exertion brightened her pale cheeks.

The lane led her to Vrisi’s village square. Breathless, she brushed the dirt from her feet; the small cuts on their soles were seeping blood, and the nylon of her stockings was in shreds. She slipped her shoes back on her feet, and glanced behind. No one, as yet, was following. Out of habit learned from her father, she looked up above the foothills, searching for airborne eagles, but the skies were empty; on the road which wound in hairpins through the pine-forests, nothing moved.

She walked slowly towards the heart of the square, where a statue stood on a plinth engraved with her father’s name – Santos Volakis, Poet – and the dates of his birth and death. The granite figure was a bland-faced man, undistinguished, and dressed in a style of suit her father had worn only at his own wedding; it held one finger to its cheek, in an effeminate gesture her father had never made, mocking in its vacuous contemplation of a wordless book the incisiveness she had so admired in him. Bright scraps of litter lay in the hardy weeds around the statue’s base; pigeon-droppings fouled her father’s shoulders and the toe-caps of his shoes.

Along the cemetery lane, voices high with the excitement of a drama were growing close. Leda drew her coat tight round her, and lowered her head; and, trusting in this attitude to defend her against unwanted enquiry into her welfare, she set off uphill on the familiar road, in the direction of the house she had once called home.

Four Years Previously

Fence your own vineyards, and covet not those of others.

Greek proverb

Two

The audience was alive with anticipation. Most of its members had arrived early, and checked the slowly passing minutes on their watches, flicking through well-read volumes brought for signing as they exchanged pleasantries with strangers. As the hands of the wall-clock moved close to the hour, a man – somewhat overweight, and rather taller than most – took a seat amongst them, tucking a leather holdall between his feet and unbuttoning his raincoat before settling into his chair.

On the platform of the draughty hall, the Dean in all his pomposity at last rose from his seat, and spreading his arms wide as a circus ringmaster, exhorted the warmest of welcomes for the visiting speaker.

‘It is an unsurpassed honour for the university, and for the Department of Hellenic Studies in particular, to present to you our most distinguished guest. Santos Volakis has been called the finest poet of his generation, but I suggest that the innovative nature of his work, his mastery of contemporary poetic form and the beauty that he weaves from the words of our noble language might easily earn him a place amongst the greatest of all generations. Ladies and gentlemen, it is my absolute pleasure to introduce him to you now – Santos Volakis!’

Clapping his fleshy hands together, red-faced and beaming, the Dean led the light (though enthusiastic) applause from the forty-two people before him, and sat down on his carved-backed chair before a bust of an ageing Homer.

Through the hall’s high windows, rain dribbled from broken guttering to the lintels, and splashed into pools spreading across the car park. Behind the platform’s long, oak table, Santos Volakis stood, opened up a slim volume at a page marked with a strip of yellow paper, and slipped his hands in the pockets of his gabardine trousers, stooping as though his back carried some burden, his head low, as if he bore some grief. Too young by at least a decade for grey-haired gravitas, he cultivated that quality through an older man’s style of dress – a brushed-cotton shirt, a waistcoat lined with silk, a jacket with the elbows patched in ovals of green leather – and as a mark of his creativity, wore his hair down to his shoulders. With languorous abstraction, he brushed stray strands from his eyes.

‘Thank you,’ he said. ‘I shall read, if I may, from Songs from Silence, my latest collection. And aiding me with a dramatic interpretation of my work, my lovely daughter, Leda.’

Leda stepped from behind a stage curtain of faded velvet, slender in a gown of powder-blue chiffon, satin ballet shoes tied with ribbons on her feet, her hair pinned up in an elaborate arrangement of ringlets. She brought with her to the stage two masks, mounted on silver rods: sinister, porcelain faces drawn from the dramas of ancient Greece, one showing the despair of Tragedy, the other – which she held up to conceal her own face – Comedy’s ridiculing grin.

The clock on the wall ticked away the expectant seconds. At first, the poet seemed to have no intention of beginning. He looked down at his audience, regarding them as if th

ey were curios on display, until his eyes fell on a young girl in the front row, at whom he smiled. Then, with only a glance at the pages of the open book, he began his recitation. In unhurried, seductive tones as dark as chocolate, his mesmerising verses span webs of erotic craving and love, of loss, grief and regret, of fierce patriotism and stirring longings to be carried home. And as he spoke, Leda gracefully mimed the poem’s sentiments, illustrating through artful movements the subtle nuances of her father’s words, from time to time switching masks, always whilst her back was to the audience, so her own face was always hidden by a false smile, or a bogus frown.

At the end of each poem, there was a pause, which seemed to wake the poet’s listeners from the dreams he had inspired and prompt them to eager applause. As he turned the page to each fresh poem, he surveyed his audience with arrogance, assessing their ability to grasp the finer shades of meaning in his verses; and wherever he had doubts, he turned the page again.

For forty minutes, he went on in this way – reciting, captivating, judging, moving on – until he finished the last poem in the volume. Sighing, he closed the book, said ‘Thank you,’ and sat down, as Leda slipped away behind the curtain.

In a light sweat of excitement, the Dean tugged at his bow-tie to loosen it, and rose once more from his seat.

‘Marvellous!’ he said. ‘Breathtaking, absolutely! Such a privilege for all of us to hear that astonishing work read by the man who created it. And Kyrie Volakis has very kindly agreed to stay with us a while, to answer your questions and sign copies of his books, which are on sale at the back of the hall. Now, will you please join me in thanking him once again in the accustomed manner? Ladies and gentlemen, Mr Santos Volakis!’

The Dean ushered the poet off the platform and through the hall. The people who had been his audience stood back, and watched the poet curiously as he passed, as if surprised to find him merely human.

The Bull of Mithros

The Bull of Mithros The Feast of Artemis (Mysteries of/Greek Detective 7)

The Feast of Artemis (Mysteries of/Greek Detective 7) The Taint of Midas

The Taint of Midas The Doctor of Thessaly

The Doctor of Thessaly The Whispers of Nemesis

The Whispers of Nemesis The Messenger of Athens

The Messenger of Athens